Standard Libraries. The concept is straightforward; A Standard Library is a set of Forms, Data Dictionaries,

Edit Checks and other study design elements which can be used as building-blocks to assemble an EDC study design. Using

a Standard Library should increase efficiency, eliminate variation, reduce study build times and therefore reduce cost.

The reality is not always so straightforward. Standard Libraries require maintenance and they require enforcement to

ensure that they are being used correctly and these activities are not free. For CRO's providing EDC study build

services where every client Sponsor has one or more Standard Libraries, managing compliance can be a major challenge.

Medidata Rave Architect provides Global Libraries to organize standard design objects and a Copy Wizard to quickly

pull those objects into a study design. These are useful tools for the Study Builder but really only cover the

initial phase of study build. Lets look at an example of Standards in action to see how TrialGrid extends the

capabilities of Rave Architect to support the use of standards through the entire study build.

A Standard Form

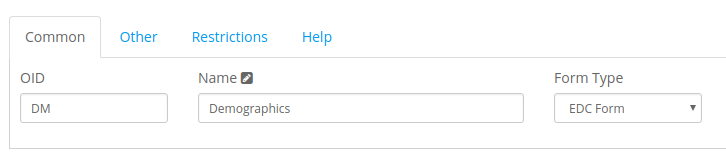

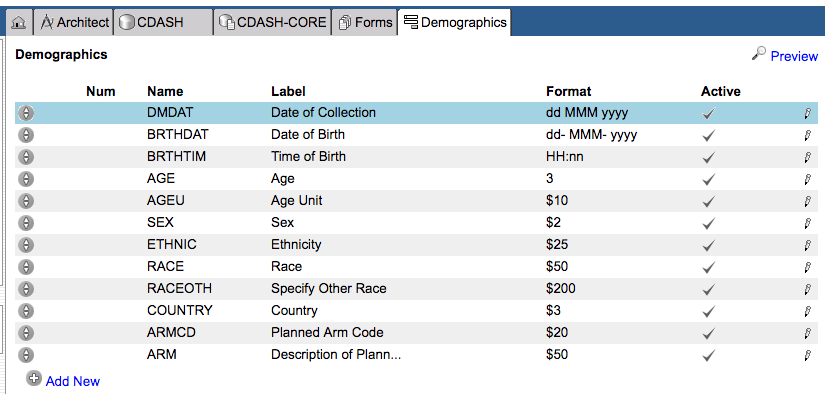

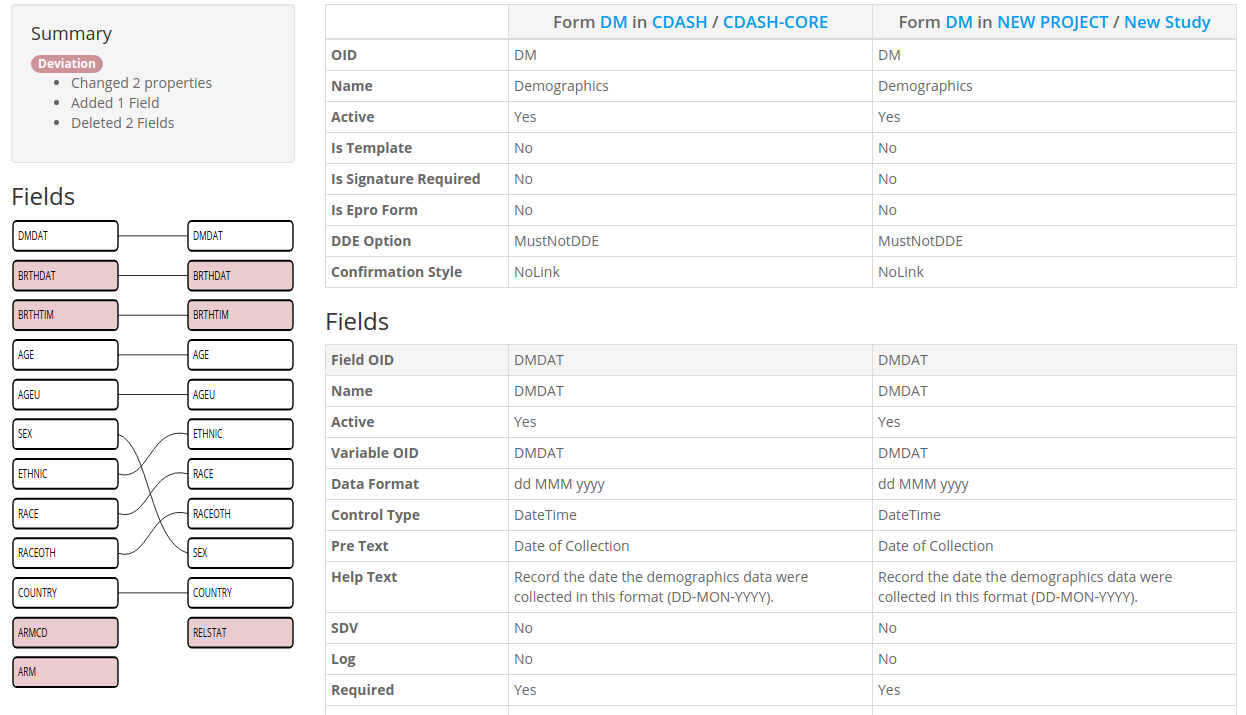

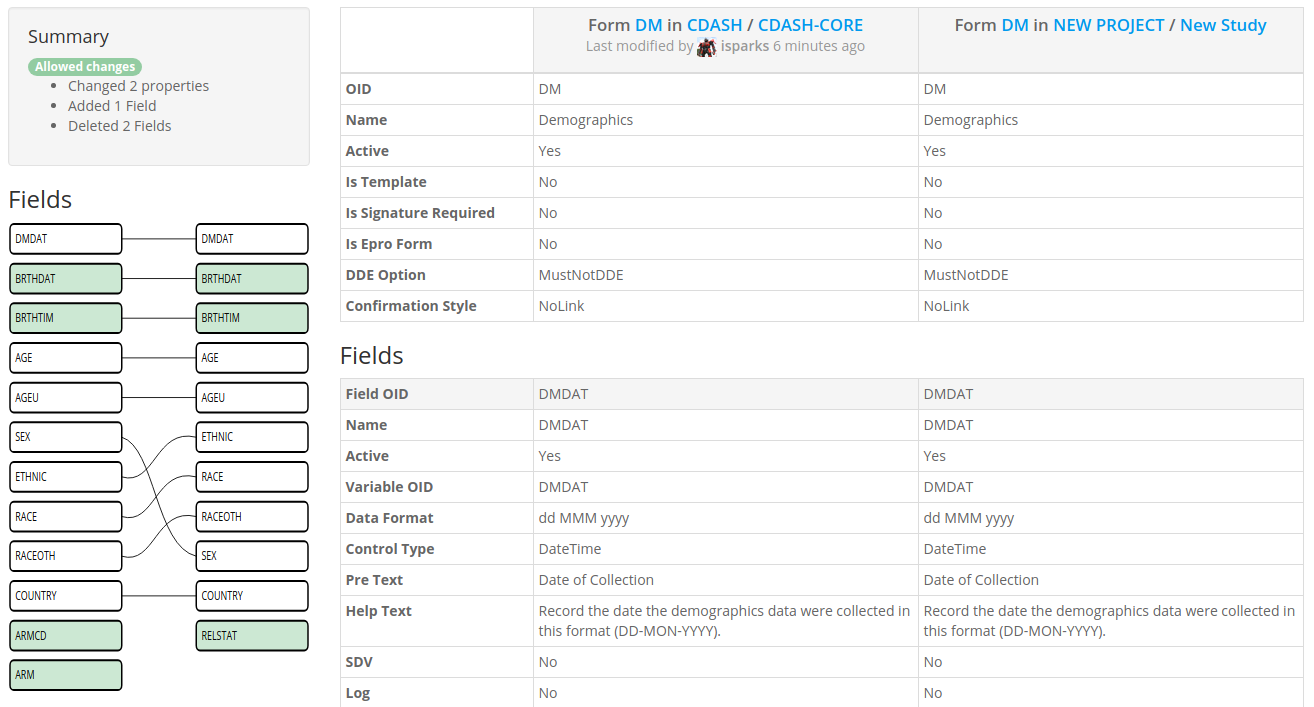

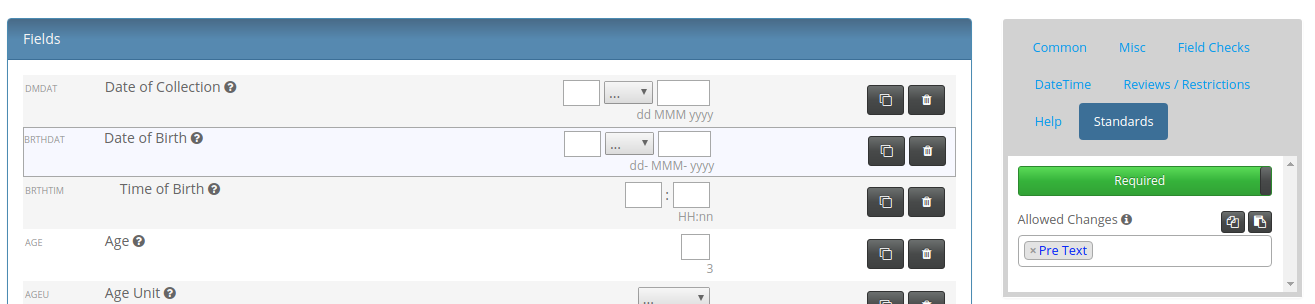

We'll start with an example standard Form, loosely based on the CDISC Demography Form. Here is the

design of the form in Architect.

This is the Form definition which is copied into a new study.

Changes to the Standard Form

In many cases a "Standard Form" will have some allowed changes. Some Fields may be optional, some Properties

of Fields such as their Labels or Help text, may be allowed to be changed. Making these changes may not

be considered a deviation from the Standard.

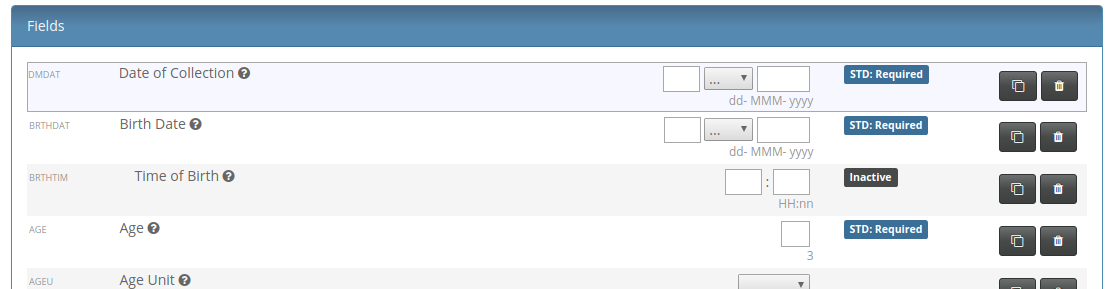

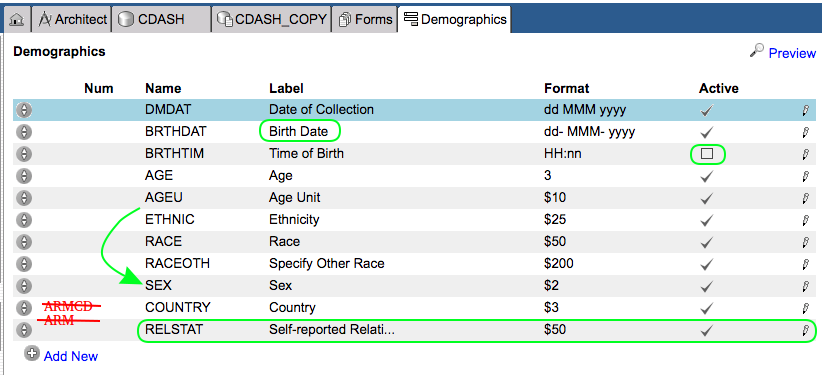

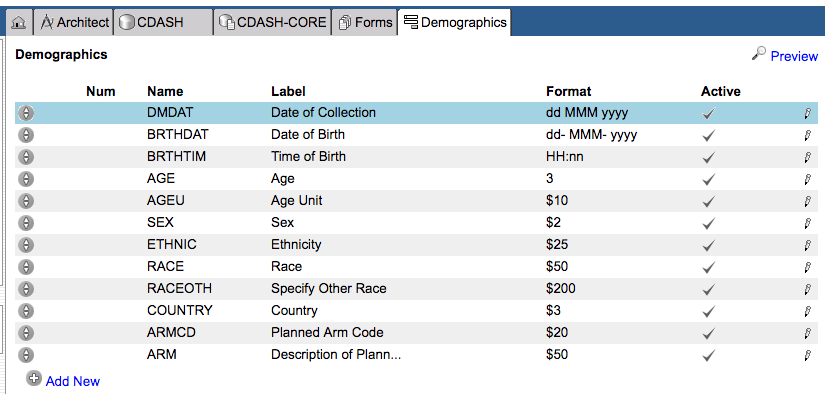

The following changes are made to the Standard Form by our Study Builder:

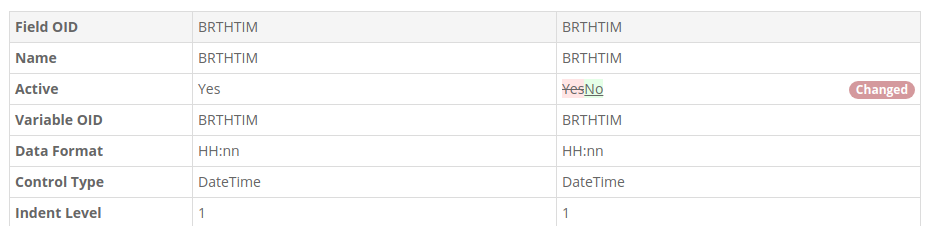

- The Time of Birth field is made inactive (invisible, not collected)

- The Sex field is moved down the field order so that it appears after Race

- Planned Arm Code and Arm are removed altogether from the form

- The field label for Date Of Birth is changed to "Birth Date"

- A new field, RELSTAT : Self-reported relationship status, is added to the Form

It now looks like this (changes highlighted):

Challenges

The challenge for the Standards Manager and for the Study Builder is to determine if the changes that have

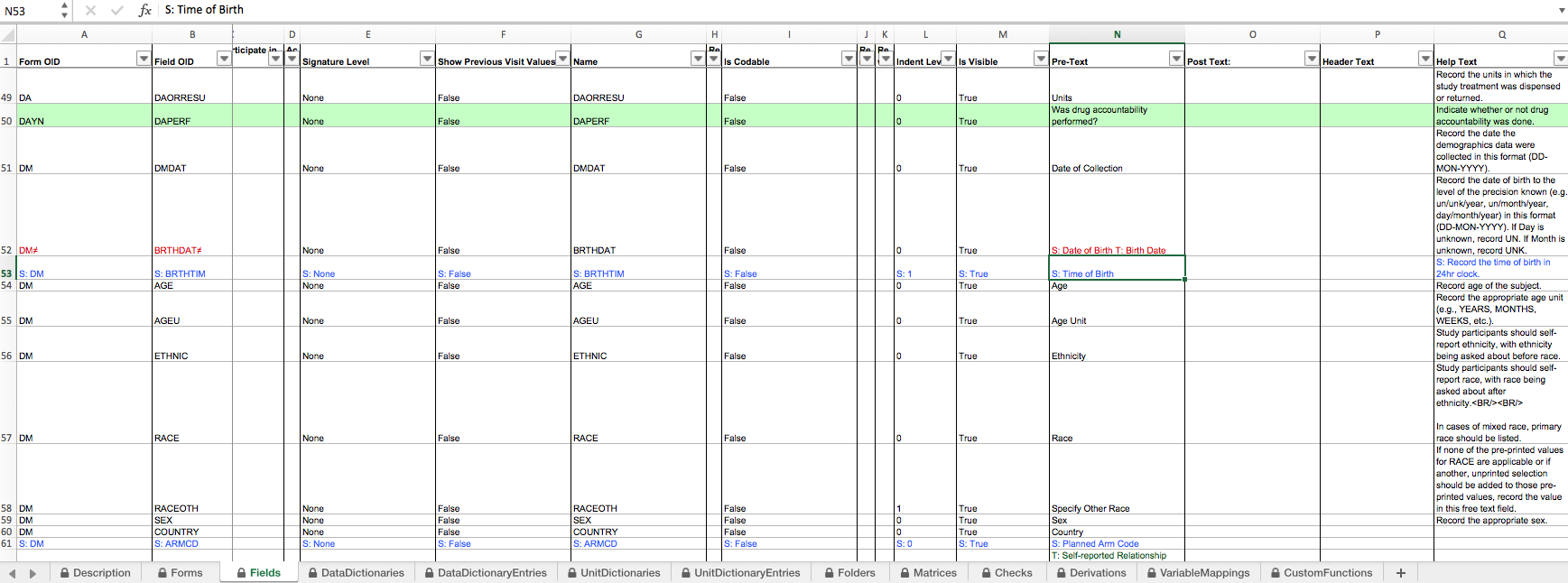

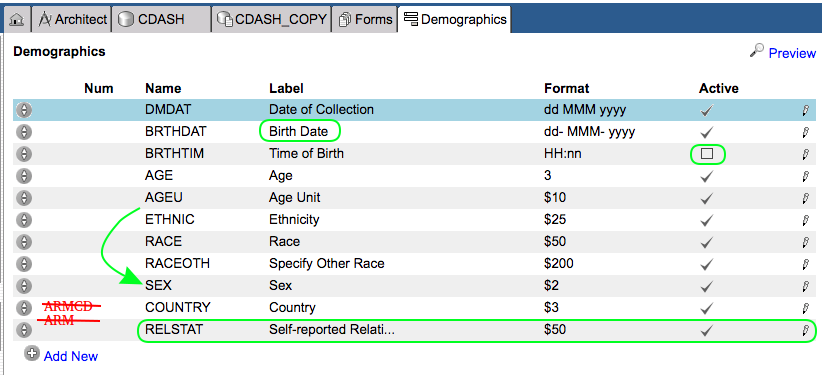

been made to this Form make it non-compliant. The Rave Architect Global Library stores the original Form and

Architect provides a difference report which can help to determine the differences between the Form as pulled

from the library and as-modified in the study:

The color coding shows that changes have been made to the Fields of the DM Form but it is difficult to read in the

spreadsheet format and Architect doesn't have any concept of what changes are allowed to a Form or to Field properties

so cannot be any help in determining if these changes are OK (compliant with Standard) or not (non-compliant).

If your process requires these kinds of changes to be reviewed by a Standards Manager or otherwise compared against a

set of written rules for the use of the Standard this can become a very time-consuming activity, stretching timelines

and increasing costs.

The TrialGrid way

TrialGrid is a system that brings together Standards Compliance, Study Design and Quality checking into a single

integrated environment. So how does it manage the Standards Compliance workflow?

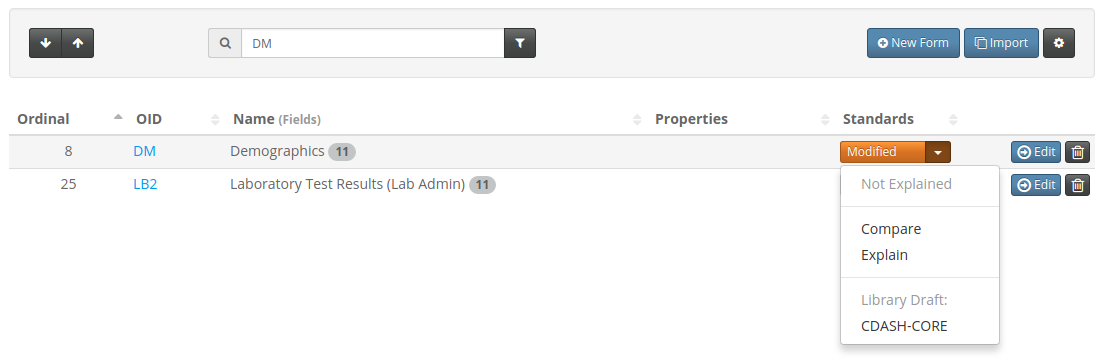

First we'd import both the Global Library Draft and the Study Draft into TrialGrid. It takes about 30 seconds to

download an Architect Loader Spreadsheet from Rave Architect and about 30 seconds to load one into TrialGrid. In two

minutes we can have the library and study draft uploaded into the system.

Next we mark the Global Library Draft as a Library and we link the Study Draft to it, actions that take about

5 seconds to perform.

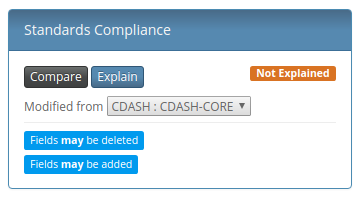

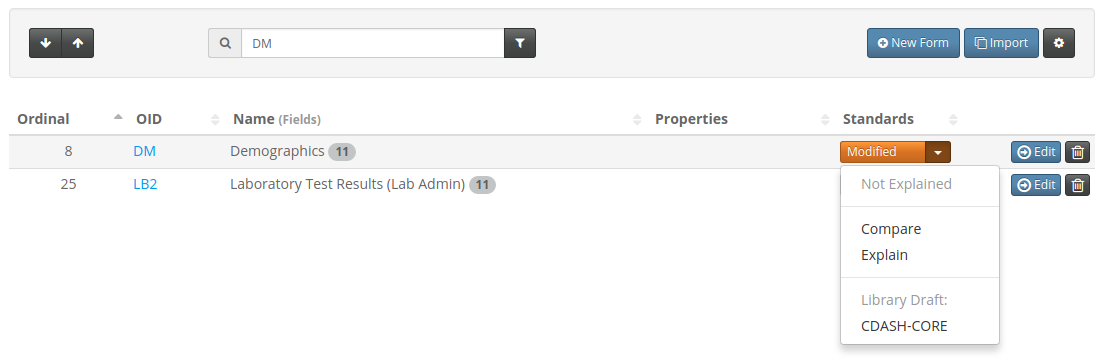

Immediately the Form list shows that the DM form has been modified from the standard and that the

changes are unexplained:

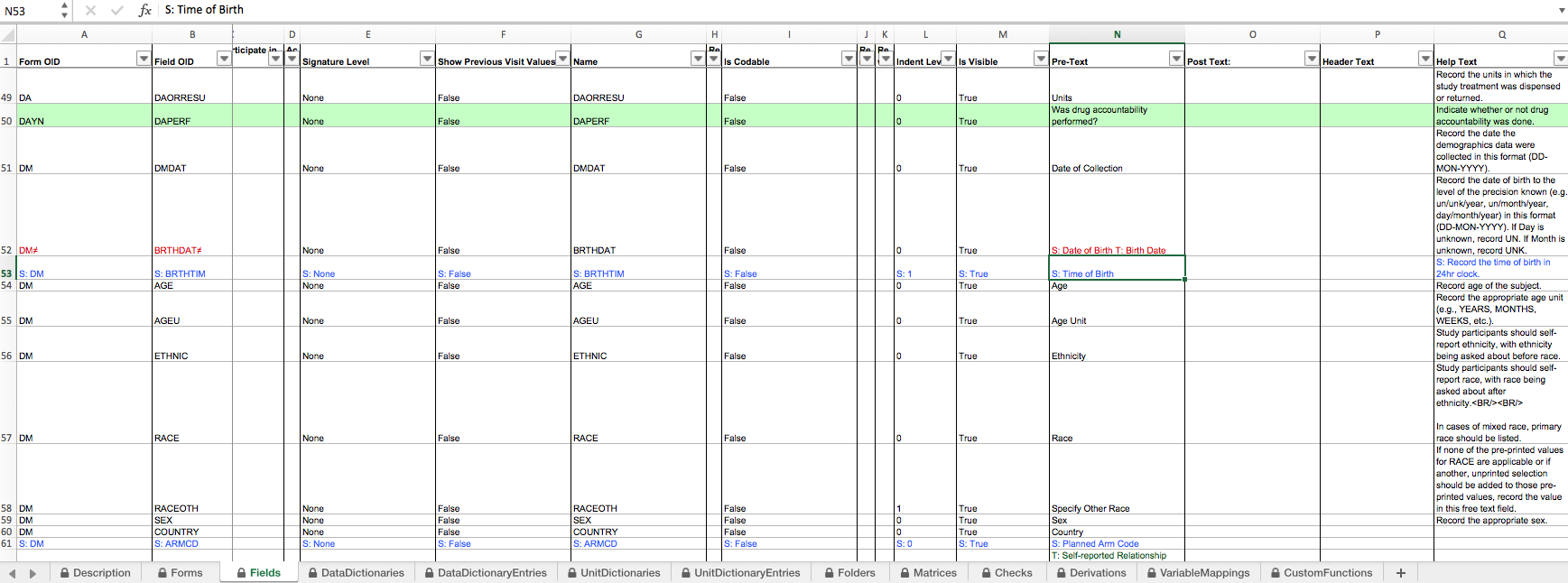

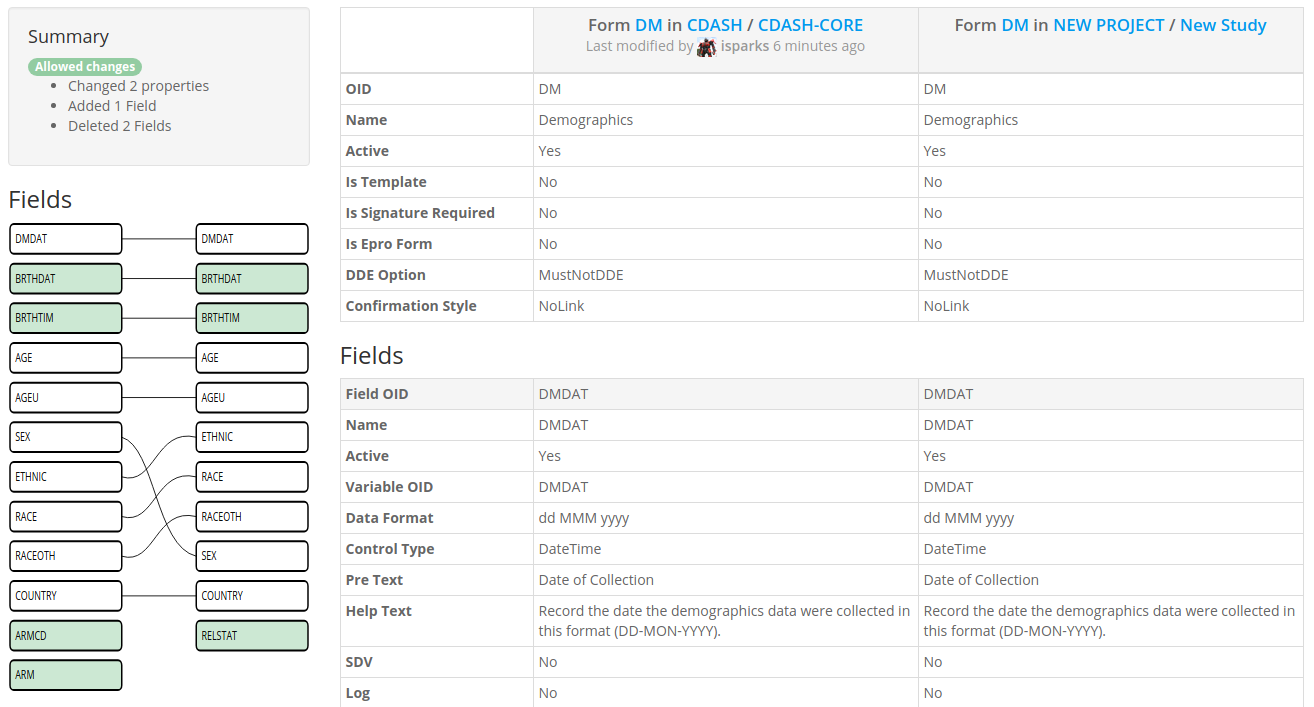

So what are those differences? Click the Compare button to find out:

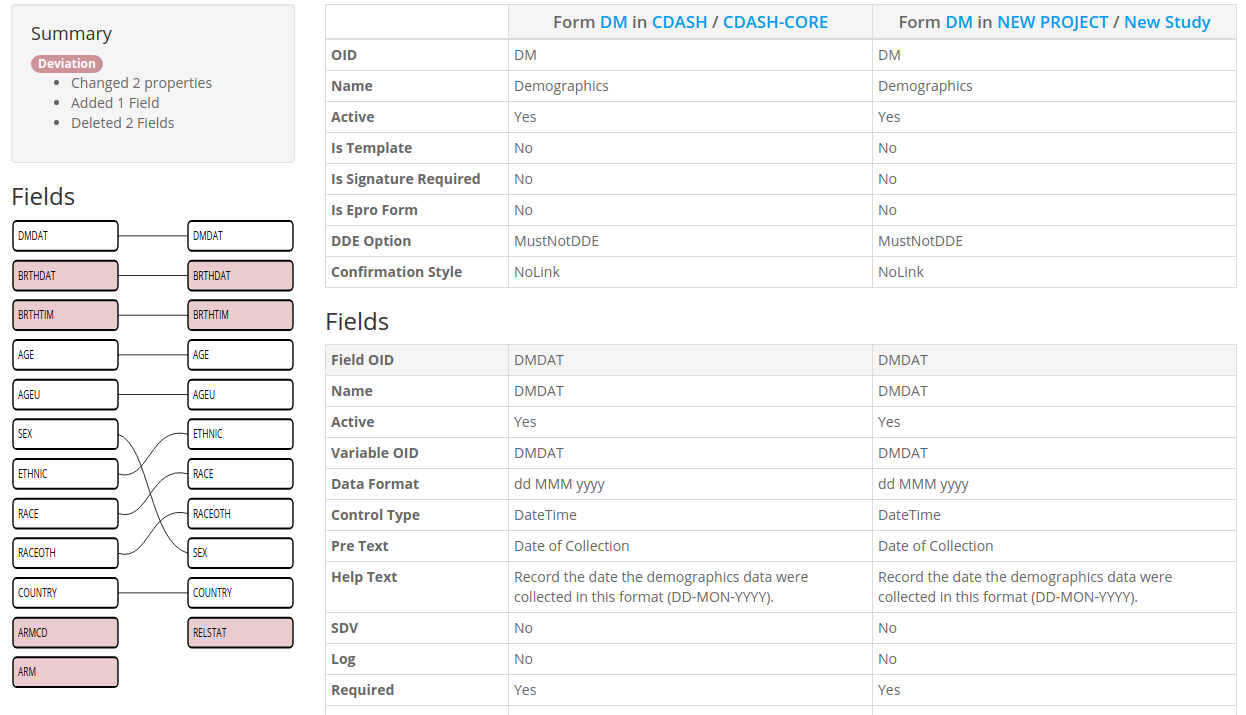

In the top left we see a summary of the changes which tells us which changes, if any, are deviations from the Standard.

Below is a graphical representation of the Fields of the Form with the Standard on the left and the current Form on

the right. Changes are colored in Red and lines between the Fields show how they match up. We can quickly see which

Fields have changed and which have no equivalent between the Standard and the New. Fields which have been moved in

the order are also clear to see, we can see that SEX has been moved down below RACEOTH in the new Form.

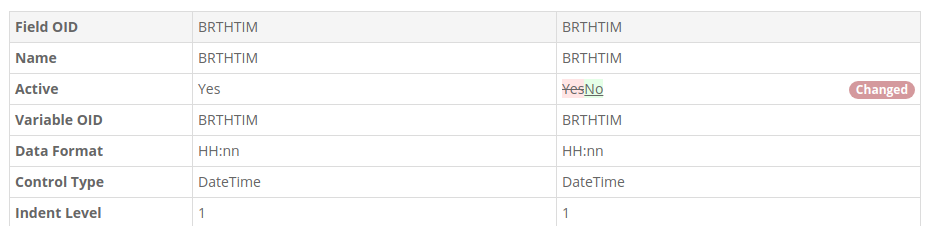

Clicking on any of the Field boxes takes the user to the Properties with any changes highlighted.

Allowed Changes

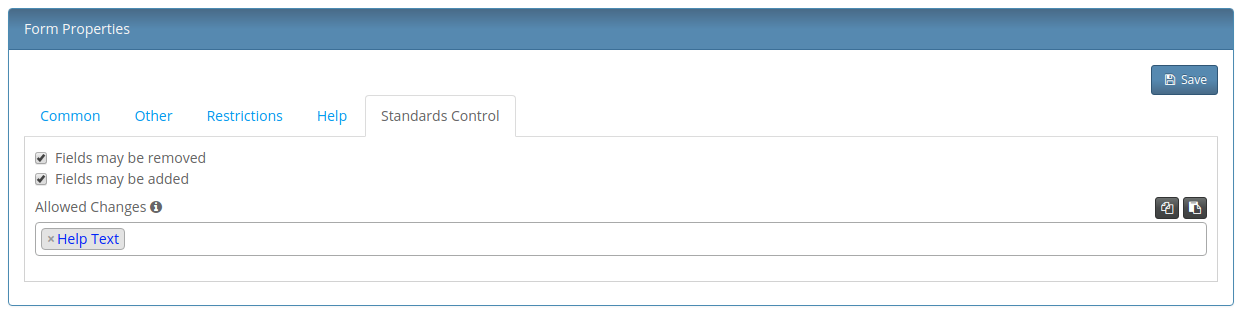

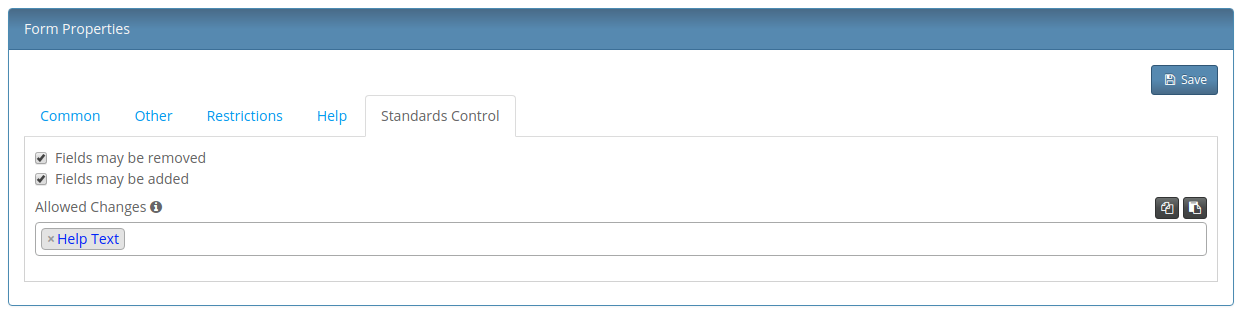

So far we have demonstrated that TrialGrid makes comparisons between objects easier but what about Allowed changes?

In order to set that up we need to navigate to the Standard Form. Here we can select the Standards Control tab and

set some global options for the Form. In this case we're saying that the Form Help Property can be changed

and that Fields may be Removed and that Fields may be added.

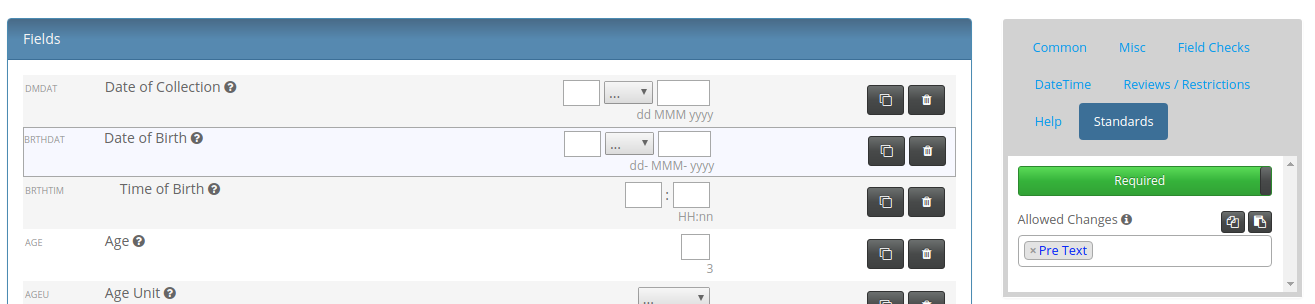

But there are some Fields we do not want to be removed such as Date of Birth. We can override this option

for the Date of Birth Field. If our standard allows it we can also select properties which are allowed to be changed.

Here we select "Pre Text" (the question label) as an allowed change and mark the field as Required by the Standard.

Finally, for Time of Birth we can allow the Active property to be changed (not shown in screenshot).

Now when we return to the Comparison view we see that all our changes are now shown in green.

If you recall from the start our changes were:

- The Time of Birth field is made inactive (invisible, not collected) - Made an allowed change to the Active Property to this field.

- The Sex field is moved down the field order so that it appears after Race - Shown in the comparison (allowed by default)

- Planned Arm Code and Arm are removed altogether from the form - Form allows fields to be removed (unless they are marked required)

- The field label for Date Of Birth is changed to "Birth Date" - Field allows changes to the Pre-Text property so this is now OK

- A new field, RELSTAT : Self-reported relationship status, is added to the Form - Form allows additional Fields to be added so this is now OK.

Summary

The goal of this post was to demonstrate how the Standards Compliance features of TrialGrid assist study teams in

tracking compliance without having to use the Architect Difference Report. The Allowed Changes feature reduces

the workload on the Standards Manager or Global Librarian so that they do not have to manually review and approve

every tiny change to any element of a Standard Form.

There was no space in this post to go through the workflow for Standards Compliance approval requests and the

reporting aspects of this feature, I'll save that for a future post. If you are interested in seeing more of this

feature, please contact us.